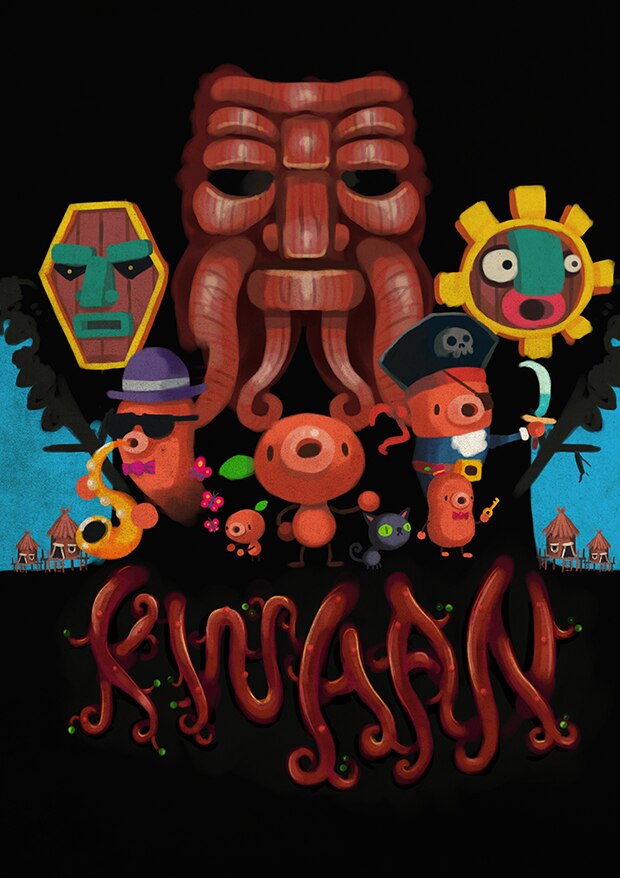

Once upon a time, there was a game far from the beaten paths of the Krosmoz. Kwaan, developed by Ankama’s Montreal studio, offered a unique experience: a multiplayer cooperative game where competition gave way to collaboration, and violence was replaced by the creation of a harmonious ecosystem. Yet, despite its bold innovations and concept, this mystical project quietly faded away in 2017, after less than three years of existence.

A look back at the story of a fascinating experiment that never managed to win over the masses. This feature is part of a retrospective series on Ankama’s various projects, following our previous focus on the mobile game Wakfu Raiders.

The Scientific Origins of an Atypical Creation

The story of Kwaan began long before its conception as a video game. The project has its roots in the academic research world, born from a collaborative project called Sensomi, co-financed by the PACA Region and ADEME as part of the AGIR program, which ran from April 2011 to December 2013. This scientific genesis largely explains the game’s unique approach.

Benoit Delassus, an intern and programmer on the project, revealed in an interview that the original idea was even more ambitious: “It started with two people (…), Maxime and David – Maxime Plantady and David Calvo – who were already working at Ankama. They participated in a kind of competition and met someone who proposed making a game about ecology.” This initial collaboration focused on ecological awareness for children, explaining why Kwaan’s universe exudes this peaceful and cooperative atmosphere.

The Sensomi project consortium brought together diverse players: the companies Ankama Play, Sen.se, and O-Labs, as well as the social psychology laboratory of Aix-Marseille University. The regional call for projects had a dual origin, both political and energetic. On one hand, the electrical peninsula situation in southeastern France required special monitoring of the electrical grid’s stability during peak consumption. On the other hand, the regional executive wanted to support actions in the field of energy sobriety and efficiency, in addition to the ITER nuclear fusion project.

The scientific objective was ambitious: to develop an engaging playful device that connects private and public spaces, real and virtual worlds, to make the consequences of each individual action visible to players. This approach aimed to raise awareness about the consequences of energy consumption and encourage sustainable lifestyles. The game’s name, Kwaan, is inspired by the abbreviation kWh (kilowatt-hour), a common unit of energy for electricity.

First Steps: A Laboratory of Experimentation (2012-2013)

Long before Ankama’s official involvement, Kwaan was born as a passionate, artisanal project. Devblogs from the time reveal a deeply experimental approach. In November 2012, the team introduced itself simply: “Kwaan is a small MMORPG” and “Kwaan is a living world. Kwaan wants you to stay and start discovering things for yourself.”

The development process revealed a craft and community-driven approach. The team started with a homemade engine before migrating to Unity in early 2013: “We are currently migrating our code from a homemade engine to Unity.”

The first tests revealed the collaborative spirit that would always characterize Kwaan. In December 2012, the team organized its first stress tests with only 10 people: “There were 10 of us, and most of us enjoyed trying to figure out what the hell this game was supposed to be about.” This approach, where players had to discover the game for themselves, would become a signature of the project.

The devblogs reveal a fascinating phenomenon: Kwaan attracted former players of Glitch, Tiny Speck’s experimental MMO that closed in December 2012. The comments on the devblogs were telling: “I was an alpha tester for Glitch” or “Former Glitchen! I’ll try it!” The development team was fully aware of this and even addressed them with a “BIG SHOUT OUT TO ALL YOU GLITCH ORPHANS.”

By May 2013, the community had reached 100 registered people, a milestone the team celebrated: “We’re officially a Tribe, folks!” and “Welcome to all you ex-Glitchens.” This player base, though modest, was already passionate and engaged.

The team explicitly defined their creation as a challenge to conventions: “We know that promising a unique experience with an MMO is a dangerous exercise, and many hopes have been crushed by the reality of the market and the complexities of designing a meaningful experience not based on consumption and grinding.”

The core concept was revolutionary: “Kwaan is a MINUSCULE experience. It’s like a ‘Fairy in a Bottle’: it’s a miniature, it’s free, it’s an experience, just to see if we can maintain a game revolving around mystery, weird features, and pure absurdity.”

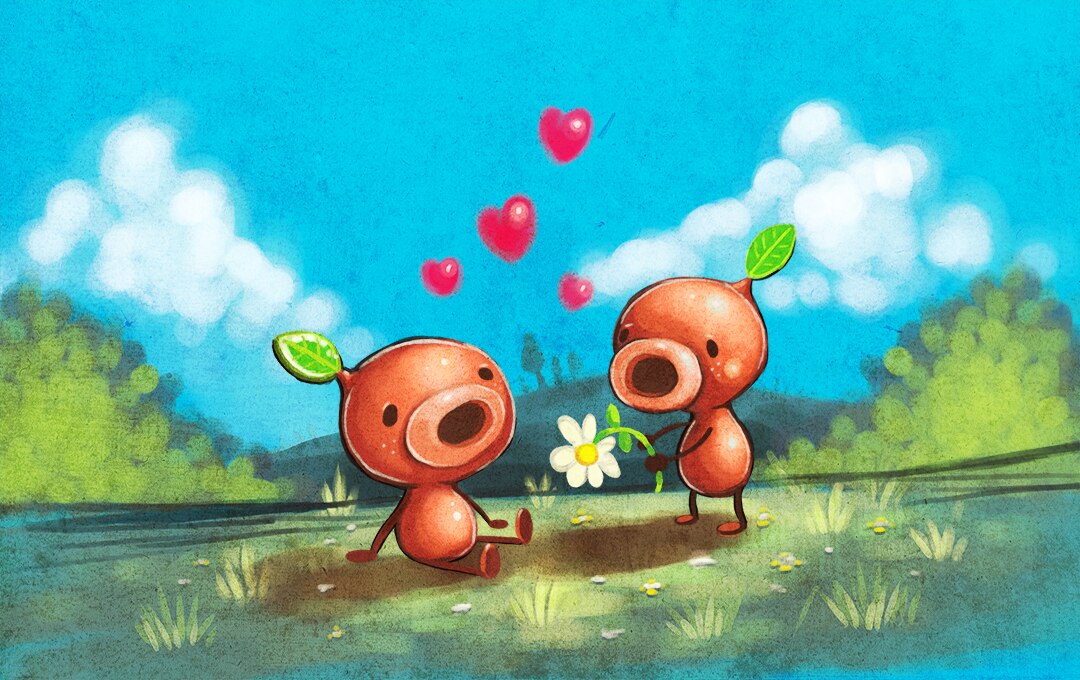

The mythological universe was dense and original. The Dwaal were described as “born from the mud of the Great Lake. They were sculpted by the hands of the Goddess and received life from the flowers she placed on their heads.” Each Dwaal possessed an Aat, a natural element that gave them their unique personality: “everything that comes from the earth, leaves, vegetables, rocks, mud.”

The Ankama Context: Stepping Outside the Krosmoz to Innovate

The year Kwaan was released, 2016, marked a period of intense diversification for Ankama. After the mixed success of Fly’n in 2012, their first game outside the Krosmoz universe, the Roubaix-based studio was actively seeking new creative avenues. Kwaan thus became the second game developed whose plot took place outside the Krosmoz.

The development of Kwaan was entrusted to Ankama’s Canadian studio, based in Montreal. According to Benoit Delassus’s thesis, “the creative aspect at Ankama is defined as ‘the engine of the company’ according to Tot” and “It is also clear that if Ankama had not had this inclination for creativity, the Ankama Play studio and the game I was able to work on: Kwaan, would never have seen the light of day.” This ultra-reduced structure contrasted with the 500 employees of the parent company in France, creating an indie studio atmosphere within a large company.

Eric Léveillée, also a programmer on the project, confirmed this creative autonomy: “We had good technology, the other developers with me did great work. But when we got to the end, just before release, we were able to bring together everything we wanted.”

Anecdote: When Tot and Kam Crossed the Atlantic

At the end of August 2014: Anthony Roux (Tot) and Camille Chafer (Kam), the founders of Ankama, accompanied by a full team of about ten people, crossed the Atlantic to work directly on the project in Montreal.

As Benoit Delassus recounts in his thesis: “The idea was to leave the Lille offices, where the atmosphere was not exactly the same, to work for two weeks on the project in a fully effective way.” This exceptional relocation testified to the personal commitment of Ankama’s creators to this experimental project.

The immersion was total for the young intern: “I discovered real enthusiasts, who worked a lot and fully committed themselves to their project. All in an atmosphere that was far from rigid and serious. It gave me a good insight into the way of working that we ourselves would have throughout the project. It was, in a way, a sharing of Ankama’s work spirit, in a privileged context.”

This visit also revealed the unique managerial philosophy of Ankama’s founders. Delassus noted: “They chose to remain active creators rather than enter the managerial aspect of such a large company. This stance marked me (…)” This approach partly explains why Kwaan benefited from direct supervision rather than remote management.

The project follow-up did not stop there: the thesis revealed a system of bi-monthly reporting with “regular reports, about every two months, with Anthony Roux, to take stock of the project’s progress, its general direction, and its results.” This close supervision confirmed that Kwaan was not just a project of the Canadian studio.

The Creative Team and Its “Organization”

The interview given to GameQuest revealed the identity of the creators of this unique experience. Kwaan was imagined by David Calvo and Maxime Plantady, two Ankama veterans who had been working at the studio for about ten years and had notably developed Islands of Wakfu on Xbox Live Arcade.

The Montreal team was completed with Mathieu Giguère as graphic designer, Benoit Delassus and Eric Léveillée as game designers, as well as renowned external collaborators: Gary Lucken as art director and David Kanaga as music composer.

Eric Léveillée described his role in the team: “I worked on three projects. First, I worked on Abraca […] then I worked a little on Tactile Wars, which was my first mobile game experience. After that, I worked on Kwaan, which was my main experience.”

The creative philosophy of the team was evident in David Calvo’s statements: “Our desire was first to create a small world – we like the idea that virtual worlds are spaces that exist in another dimension and that we discover through our computers.”

Benoit Delassus’s thesis revealed aspects of the organization of the Montreal studio. Unlike rigid development methods, the Kwaan team operated according to deeply flexible principles: “It is clear that the organization of our team was not of exemplary rigor and rigidity.” The weekly Scrum meetings were held briefly each morning to coordinate the team, but it was in the spontaneous brainstorming sessions that the magic happened: “they appeared completely spontaneously and informally, very often at the end of the day.”

“The morning muffins, the Friday lunches, the Wednesday croissants”

A Revolutionary Concept: Cooperation as the Only Way

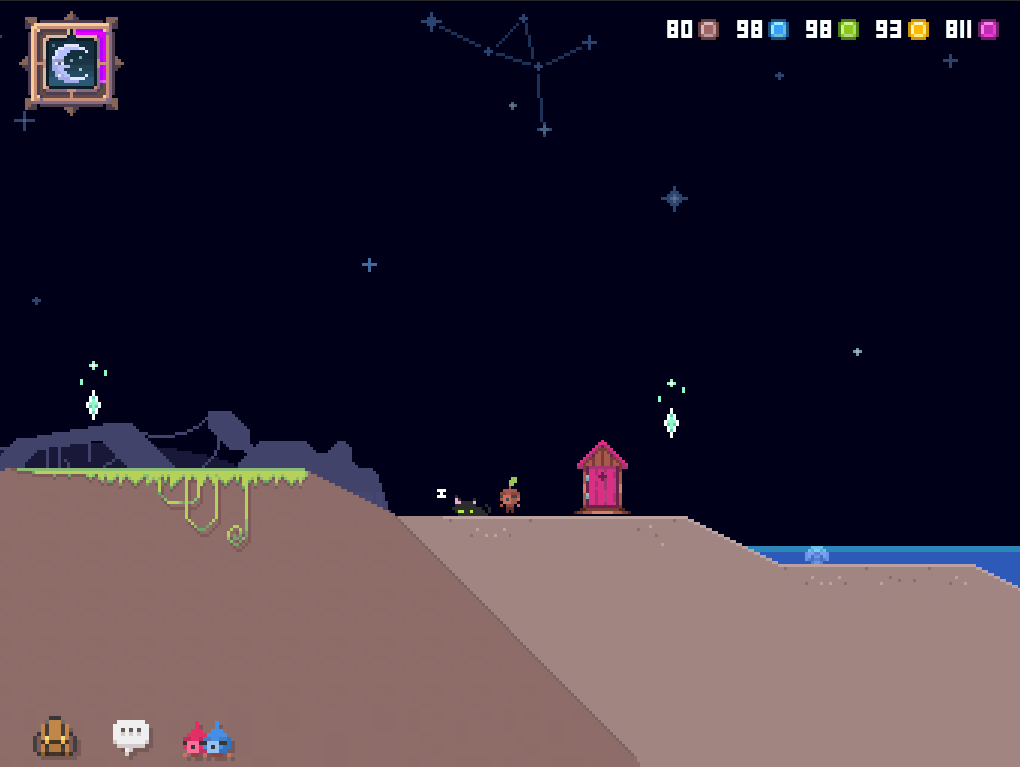

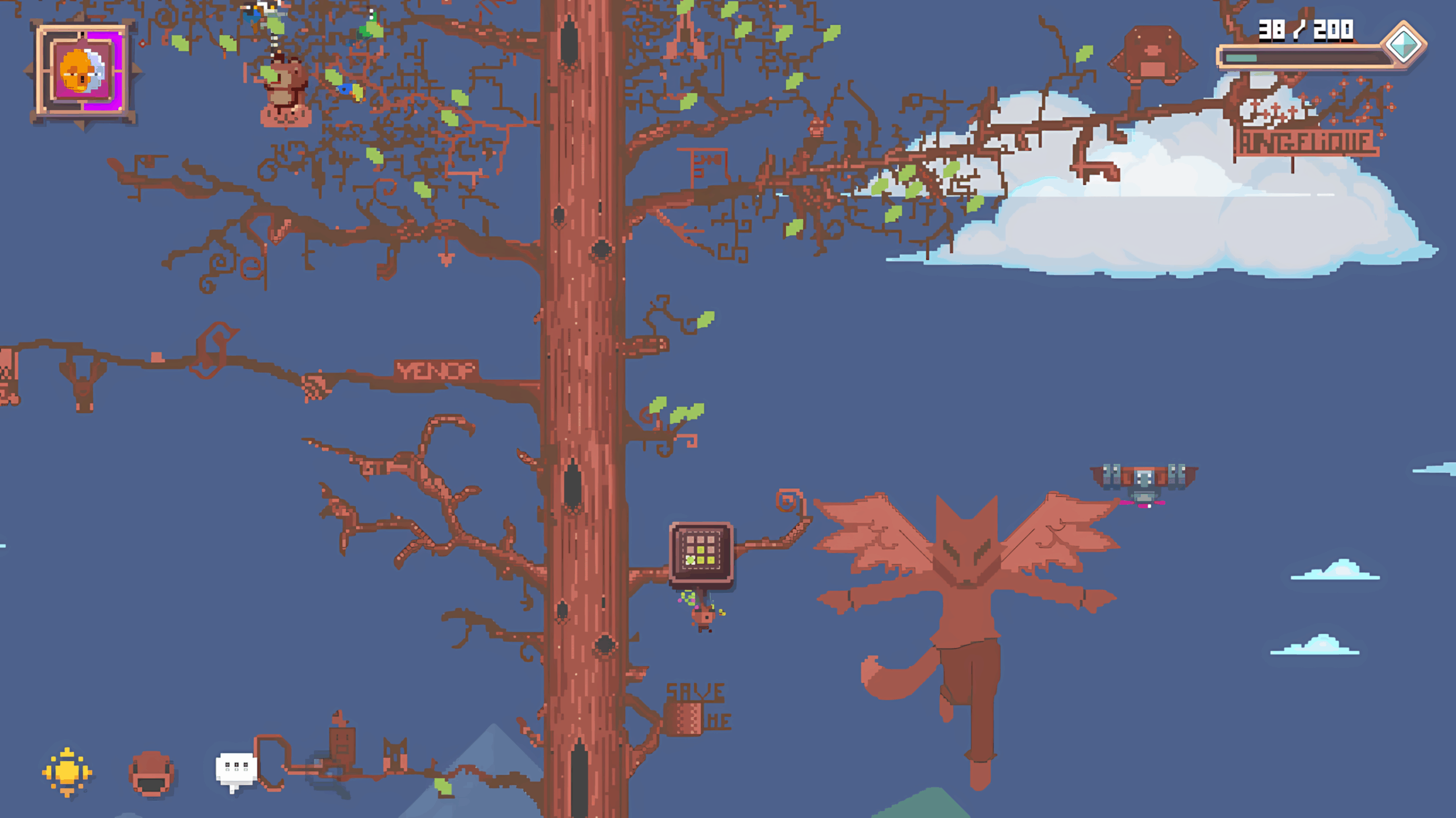

The basic principle of Kwaan radically broke with the established codes of multiplayer video games. Players embodied small plant creatures called Dwaal, special agents of nature whose mission was to keep the Kwaan, a mystical World-Tree, healthy. This collective responsibility was at the heart of the experience: no combat, no trade, no competition, but pure cooperation oriented towards a common goal.

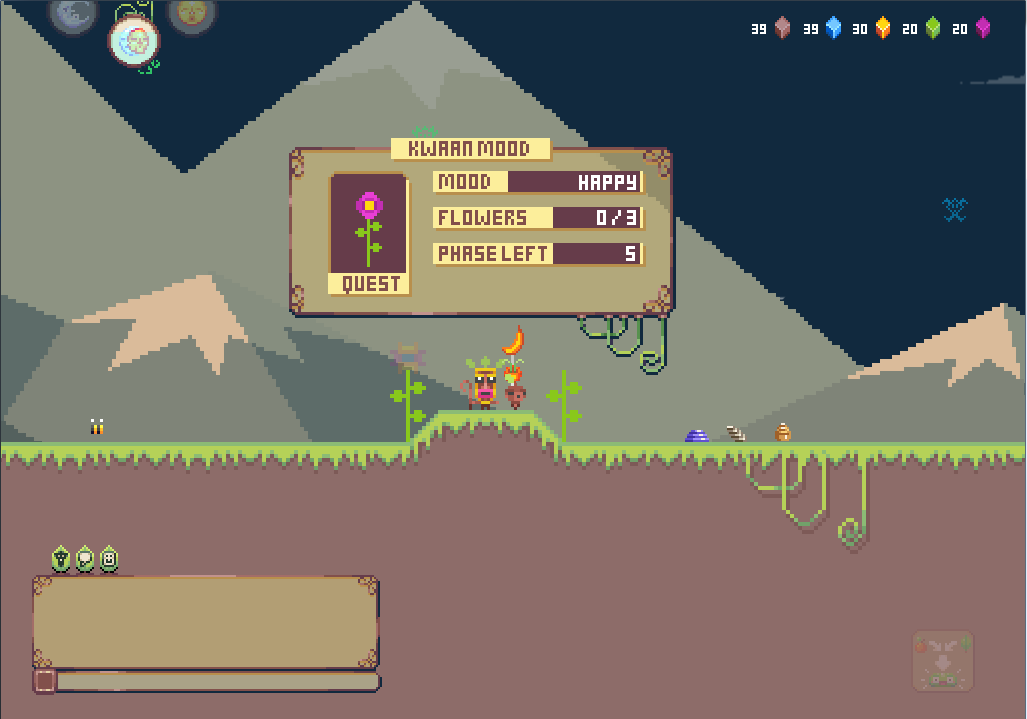

Eric Léveillée specified the game’s vision in his pitch: “The game is an online multiplayer adventure and the goal of the game is that, with a community of other players, you must keep the tree happy. Because if you don’t perform rituals every day with other people, if you don’t do it, then the server eventually dies and you lose all the progress you’ve made.”

Benoit Delassus developed this fundamental mechanic: “The first goal for each server is to ensure that their world survives. These are quests that must be redone every day on a 24-hour basis. And so, we have what we call rituals, which are cooperative missions.” These daily rituals created a natural rhythm that forced players to log in regularly and coordinate their efforts.

The most radical aspect of the system was revealed by Benoit: “And if we don’t succeed, it loses its mood and if it becomes sad to death, the game stops because the server dies […] There were six servers at the game’s launch. Four of them died.” The mortality of the servers dramatically illustrated the challenges posed by a gameplay entirely dependent on cooperation.

The mortality of the servers was a major structural problem. Benoit explained: “Originally, we wanted the server to restart directly, but then we thought that if the servers are dead, it’s because there was no one to take care of them.”

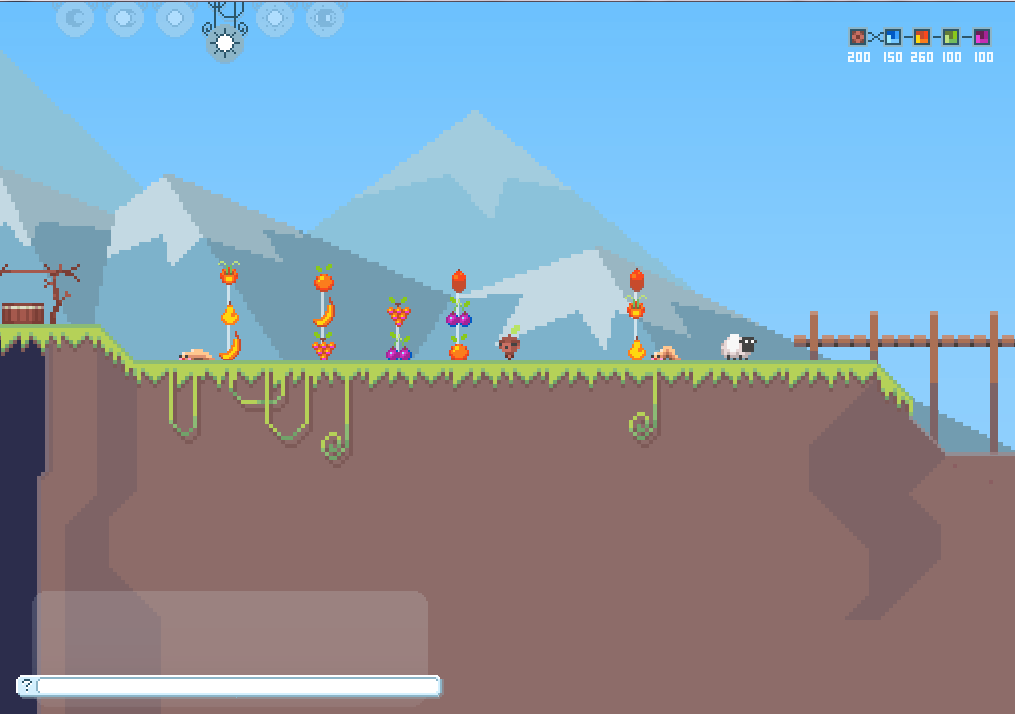

One of the most innovative aspects concerned the autonomous ecosystem described by David Calvo: “One thing we are very proud of is that Kwaan produces its own pollution – crafted objects can rot – and players can eat the rot and then digest it. It’s part of the system’s autonomy to make it more ‘alive’.”

Benoit Delassus described the narrative approach: “For now, there are only four that run in a loop. Every 24-hour day, a new story appears. Then it creates events in the world.” These cyclical stories were theoretically supposed to be regularly enriched to maintain player interest. The initial ambition was considerable: “We started with a base of 365 (…) We started with a base of cycles and once the game was perfectly finalized in this dynamic, we would only have to add stories.”

The gameplay mixed several genres in an original way: point-and-click, platform, and RPG. The Dwaal could not jump, a constraint that forced players to use a grapple to cling to surfaces and reach elevated platforms. This unique movement mechanic created a different approach to exploration, where every move had to be calculated and cooperation became natural to access the most difficult areas.

Delassus’s thesis revealed precise technical details about Kwaan’s development. The game was built on Unity with scripts developed in C# under Visual Studio. This modern technical base allowed for crucial development flexibility for experimentation. The team used Ankama’s in-house tools: one for the world map and another for multiplayer networking. For the user interface, the team opted for Flash, while the graphics were created under Photoshop. This hybrid technical architecture allowed for rapid adjustments.

One aspect of Kwaan’s development was the exceptionally close relationship between developers and players. Eric Léveillée described his daily approach: “I was very close to the community in the game; we had a lot of interactions with them. For example, in the morning, the first thing I did was launch the game. Kwaan has public servers, so we could go on all the servers; I would go on a server.”

Benoit Delassus confirmed this philosophy: “We really focused on cooperation between players. It was one of the first blocking aspects of the game because cooperation implied that players had to teach each other. There was no tutorial at the beginning of the game.” This deliberate absence of a tutorial forced community interactions and created authentic bonds between players.

This philosophy had its roots in the pre-Ankama period, when the team already declared: “Keep in mind, however, that the game is a mystery and it’s your role to solve it.” The original devblogs testified to this collaborative approach from the design stage: “Part of the game is actually making the game as you go along.”

The team’s responsiveness impressed the community. Eric Léveillée explained: “Often, I would talk with the players and draw sketches, then five minutes later in our code, the rules were fixed and corrected. It was as simple as that.” This development velocity was made possible by the small size of the team and the game’s flexible technical architecture.

Presentation and First Impressions

Kwaan made its first public appearances at several renowned festivals, notably PAX East in Boston in March 2015. Eric Léveillée had a memorable experience of this event: “For me, it was one of the peaks of my career. It was really interesting; we went to present the game at PAX in Boston.”

The approach to presenting the game contrasted with industry standards: “We really did it with the idea of bringing Kwaan’s zen atmosphere. Everywhere, it’s very flashy, with lights, noise to try to attract people. We did the opposite; it was more like an oasis of peace. We had our beautiful background with all the beautiful pixelated souls of the game, and we had bought small benches with cushions.”

The success of this approach was palpable: “The problem – a beautiful problem – is that it worked so well that we sometimes had lines of people waiting to play the game.”

Delassus’s thesis provided precise figures on this presentation: 250 codes distributed and 20 interviews. These figures testified to the significant media impact of the event.

The game entered early access on March 11, 2015 on Steam, before its official release on January 21, 2016 for PC, Mac, and Linux. Benoit Delassus specified: “In fact, I arrived at commit number 63 and now we’ve reached 980,” testifying to the development activity during this early access period.

The experimental approach during this phase was confirmed by Benoit: “Kwaan is a bit of an experimental game, and we need to put easily identifiable principles in it – like the level system. We don’t think about what we’re doing in terms of boxes or labels: the vision of Kwaan came to us almost complete.”

During the 6 months of early access, the game recorded 3000 purchases on Steam, a respectable figure for an experiment of this nature.

However, player engagement revealed the limits of the concept: of these 3000 buyers, only 1700 players remained active, a 50% disinterest rate. Even more concerning, the game’s daily routine only included 500 players playing between 30 minutes and 2.5 hours, with a maximum of 15 simultaneous players.

These figures contrasted dramatically with the peak of 21 simultaneous players in April 2015 revealed by Steam data, confirming the niche nature of the project. Benoit Delassus provided even more concerning figures in his interviews: “There are maybe 50 different players who log into the game at the moment.” This user base, though passionate, was insufficient to optimally operate the game’s collaborative mechanics.

One of Kwaan’s most notable innovations was its unique control system. Benoit Delassus explained this particularity: “The first reason, which is also the most relevant and a priori the only reason, is that the game was intended to be playable on tablets and we wanted to be able to play with one finger. In practice, on a computer, this materialized with a mouse.”

This technical constraint created interesting challenges. Benoit acknowledged: “Sure, we could certainly set up a movement system with arrow keys, but as the game is currently made, it would cause quite a few problems.” The mouse-only movement divided players, some appreciating the freedom of one hand, others finding the experience less natural than traditional keyboard-mouse controls.

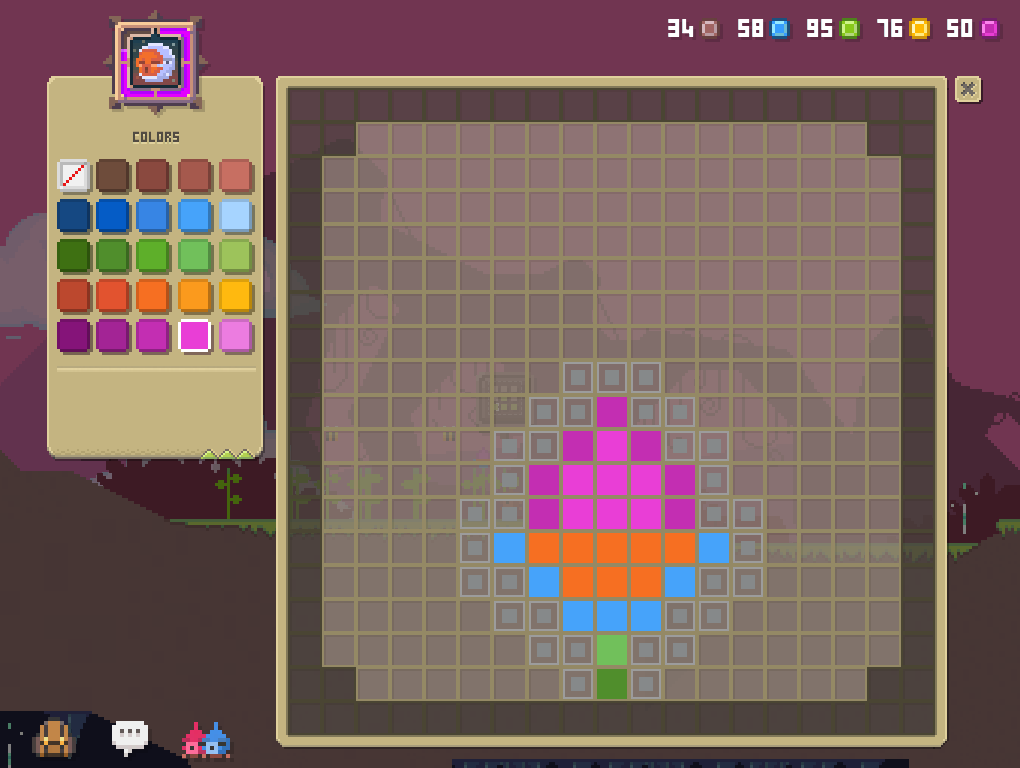

The collaborative artistic creation system was another pillar of the game. Players could express their artistic creativity by creating pixelated works in the foliage of the Kwaan tree. Benoit added: “There was notably the German community. At the beginning of the second week on Steam, we had a German with about 800,000 YouTube subscribers who made a video about Kwaan and brought in a lot of people.”

However, this creative freedom posed moderation challenges. Benoit humorously confessed to his role as a “penis cleaner“: “There were penises, and we were behind cleaning them up, and I was the one erasing them […] By the way, if you’ve seen in Kwaan, you have a character sheet and my rank is ‘penis cleaner’.”

Critical Reception and the Paradox of Visibility

The player community expressed enthusiastic opinions during interviews. In the podcast “On a juste une vie,” several players testified: “not like the others, a particularly friendly community, Ankama-style community” and mentioned “a very endearing universe with optimal accessibility.”

Benoit Delassus reported on the early access reception: “We have 31 reviews, I think. I don’t remember the exact number, but something like that for the game. And they are all positive except one.” These encouraging figures masked, however, the small user base that would prove problematic for the game’s survival.

Yet, Kwaan experienced a spectacular media moment. On January 22, 2016, the famous German streamer GRONKH, with his 600,000 followers, streamed the game for only 30 minutes and attracted 25,955 simultaneous viewers.

The barrier to entry was significant. Eric Léveillée acknowledged: “Kwaan is really a game that is not easy to get into. It’s a bit by design; we wanted it to be that way. We wanted players in the game to ask themselves and say ‘what am I doing?’” This assumed complexity created a high learning curve that discouraged some new players.

The developers had to adapt their approach in response to feedback. Eric explained: “We realized that we really needed to help players who were starting the game with tutorials.”

Identified Mistakes: Retrospective Analysis

Benoit Delassus’s thesis offered a lucid self-criticism of the mistakes made during development. The main fault identified concerned communication: “having neglected communication (…) was one of the important mistakes of our team.” This negligence partly explains why the game never found its audience despite its originality.

The communication strategy around Kwaan suffered from several limitations. David Calvo discussed the presentation challenges: “The hardest part is making players understand the depth of the game when they only see the surface – and don’t want to dig to understand why we use familiar figures to create another form of game.”

This conceptual complexity made the game difficult to present in a few sentences. Eric Léveillée‘s one-minute pitch illustrated this difficulty: “The goal of the game is that, with a community of other players, you must keep the tree happy because if you don’t perform daily rituals with other people (…) you get a community of people and you work together.” Despite its conciseness, this summary struggled to convey the richness and originality of the proposed experience.

The absence of spectacular mechanics made the game poorly suited to streaming and viral videos. Unlike action or competition games, Kwaan offered a contemplative and collaborative experience that was difficult to capture in short, impactful video formats. This inadequacy likely contributed to limiting its visibility, except for the exceptional phenomenon of the GRONKH stream, which showed that a single influencer could generate considerable buzz without converting this attention into a lasting user base.

The Closure and Its Lessons

The announced closure of Kwaan in October 2017 marked the end of a bold experiment. Eric Léveillée shared his reflections on the lessons learned: “One lesson I learned is the weight of overcomplicating things for the sake of technology or the idea, but bringing it back to the player’s pleasure. It’s something I learned a lot.”

This realization highlighted one of the project’s pitfalls: technical and conceptual sophistication had sometimes taken precedence over immediate accessibility. Eric continued: “It was my first multiplayer experience, and it was very formative.”

Delassus’s thesis offered a personal perspective on this formative experience: “This internship was my fourth in video games, and will only be the first with a finished and distributed game. But it was also the longest and most instructive, introducing me to all the stages of building a game, within a small team of passionate people.”

A Digital Ghost: The Impossible Resurrection

Today, Kwaan still exists in a particularly cruel phantom form. It remains possible to buy a Steam key for a few euros on resale sites, and these keys still activate without issue on the platform. However, this activation leads only to a bitter disappointment: after installation, the game detects no available servers and stubbornly refuses to launch.

This tragic situation highlights the total absence of community initiative to preserve Kwaan’s legacy. Unlike other cult MMOs that find a second life through fan-created private servers, Kwaan has not benefited from any community resurrection attempts. This inertia is all the more frustrating as the game had all the ingredients to appeal to creative communities.

At a time when phenomena like Reddit’s r/Place or the French Pixel War demonstrate the massive public appetite for collaborative creation, one can only regret this missed opportunity. With its gameplay based on shared artistic creation and violence-free cooperation, Kwaan could have found an audience.

The Kwaan experience probably influenced Ankama’s subsequent reflections on the balance between innovation and accessibility. The developers’ testimonies revealed a passionate team that pushed the boundaries of what a multiplayer game could be, creating an authentically collaborative experience in a landscape dominated by competition.

Kwaan remains a precious testimony of what video games can be when they free themselves from commercial constraints to explore new narrative and playful territories. Its failure in no way diminishes the value of this attempt, which enriches the creative heritage of the French industry and continues to inspire developers who refuse to settle for proven formulas.

Today, nearly eight years after its closure, requests persist sporadically: “Is there a chance for a sequel?” wondered a nostalgic player in 2019, while another pleaded in 2018 for “private servers” or an “offline version.” In 2020, a lone voice still called: “Please, bring this game back,” and more recently in 2023, someone simply asked if the game “still works.” These scattered requests, true digital messages in a bottle, testify to the lasting attachment of a handful of die-hard nostalgics who refuse to forget this unique experience. However, Ankama remains silent in the face of these community requests, leaving Kwaan definitively in digital limbo – purchasable but unplayable, a ghost of an experience that lived only for the time of a creative breath.